Country Entry: Decisions and Strategies

Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning. Segmentation, in marketing, is usually done at the customer level. However, in international marketing, it may sometimes be useful to see countries as segments. This allows the decision maker to focus on common aspects of countries and avoid information overload. It should be noted that variations within some countries (e.g., Brazil) are very large and therefore, averages may not be meaningful. Country level segmentation may be done on levels such as geography—based on the belief that neighboring countries and countries with a particular type of climate or terrain tend to share similarities, demographics (e.g., population growth, educational attainment, population age distribution), or income. Segmenting on income is tricky since the relative prices between countries may differ significantly (based, in part, on purchasing power parity measures that greatly affect the relative cost of imported and domestically produced products).

The importance of STP. Segmentation is the cornerstone of marketing—almost all marketing efforts in some way relate to decisions on who to serve or how to implement positioning through the different parts of the marketing mix. For example, one’s distribution strategy should consider where one’s target market is most likely to buy the product, and a promotional strategy should consider the target’s media habits and which kinds of messages will be most persuasive. Although it is often tempting, when observing large markets, to try to be "all things to all people," this is a dangerous strategy because the firm may lose its distinctive appeal to its chosen segments.

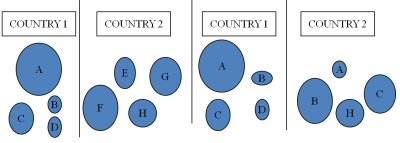

In terms of the "big picture," members of a segment should generally be as similar as possible to each other on a relevant dimension (e.g., preference for quality vs. low price) and as different as possible from members of other segments. That is, members should respond in similar ways to various treatments (such as discounts or high service) so that common campaigns can be aimed at segment members, but in order to justify a different treatment of other segments, their members should have their own unique response behavior.

Approaches to global segmentation. There are two main approaches to global segmentation. At the macro level, countries are seen as segments, given that country aggregate characteristics and statistics tend to differ significantly. For example, there will only be a large market for expensive pharmaceuticals in countries with certain income levels, and entry opportunities into infant clothing will be significantly greater in countries with large and growing birthrates (in countries with smaller birthrates or stable to declining birthrates, entrenched competitors will fight hard to keep the market share).

There are, however, significant differences within countries. For example, although it was thought that the Italian market would demand "no frills" inexpensive washing machines while German consumers would insist on high quality, very reliable ones, it was found that more units of the inexpensive kind were sold in Germany than in Italy—although many German consumers fit the predicted profile, there were large segment differences within that country. At the micro level, where one looks at segments within countries. Two approaches exist, and their use often parallels the firm’s stage of international involvement. Intramarket segmentation involves segmenting each country’s markets from scratch—i.e., an American firm going into the Brazilian market would do research to segment Brazilian consumers without incorporating knowledge of U.S. buyers. In contrast, intermarket segmentation involves the detection of segments that exist across borders. Note that not all segments that exist in one country will exist in another and that the sizes of the segments may differ significantly. For example, there is a huge small car segment in Europe, while it is considerably smaller in the U.S.

Intermarket segmentation entails several benefits. The fact that products and promotional campaigns may be used across markets introduces economies of scale, and learning that has been acquired in one market may be used in another—e.g., a firm that has been serving a segment of premium quality cellular phone buyers in one country can put its experience to use in another country that features that same segment. (Even though segments may be similar across the cultures, it should be noted that it is still necessary to learn about the local market. For example, although a segment common across two countries may seek the same benefits, the cultures of each country may cause people to respond differently to the "hard sell" advertising that has been successful in one).

The international product life cycle suggests that product adoption and spread in some markets may lag significantly behind those of others. Often, then, a segment that has existed for some time in an "early adopter" country such as the U.S. or Japan will emerge after several years (or even decades) in a "late adopter" country such as Britain or most developing countries. (We will discuss this issue in more detail when we cover the product mix in the second half of the term).

Positioning across markets. Firms often have to make a tradeoff between adapting their products to the unique demands of a country market or gaining benefits of standardization such as cost savings and the maintenance of a consistent global brand image. There are no easy answers here. On the one hand, McDonald’s has spent a great deal of resources to promote its global image; on the other hand, significant accommodations are made to local tastes and preferences—for example, while serving alcohol in U.S. restaurants would go against the family image of the restaurant carefully nurtured over several decades, McDonald’s has accommodated this demand of European patrons.

The Japanese Keiretsu Structure. In Japan, many firms are part of a keiretsu, or a conglomerate that ties together businesses that can aid each other. For example, a keiretsu might contain an auto division that buys from a steel division. Both of these might then buy from a iron mining division, which in turns buys from a chemical division that also sells to an agricultural division. The agricultural division then sells to the restaurant division, and an electronics division sells to all others, including the auto division. Since the steel division may not have opportunities for reinvestment, it puts its profits in a bank in the center, which in turns lends it out to the electronics division that is experiencing rapid growth.

This practice insulates the businesses to some extent against the business cycle, guaranteeing an outlet for at least some product in bad times, but this structure has caused problems in Japan as it has failed to "root out" inefficient keiretsu members which have not had to "shape up" to the rigors of the market.

Methods of entry. With rare exceptions, products just don’t emerge in foreign markets overnight—a firm has to build up a market over time. Several strategies, which differ in aggressiveness, risk, and the amount of control that the firm is able to maintain, are available:

- Exporting is a relatively low risk strategy in which few investments are made in the new country. A drawback is that, because the firm makes few if any marketing investments in the new country, market share may be below potential. Further, the firm, by not operating in the country, learns less about the market (What do consumers really want? Which kinds of advertising campaigns are most successful? What are the most effective methods of distribution?) If an importer is willing to do a good job of marketing, this arrangement may represent a "win-win" situation, but it may be more difficult for the firm to enter on its own later if it decides that larger profits can be made within the country.

- Licensing and franchising are also low exposure methods of entry—you allow someone else to use your trademarks and accumulated expertise. Your partner puts up the money and assumes the risk. Problems here involve the fact that you are training a potential competitor and that you have little control over how the business is operated. For example, American fast food restaurants have found that foreign franchisers often fail to maintain American standards of cleanliness. Similarly, a foreign manufacturer may use lower quality ingredients in manufacturing a brand based on premium contents in the home country.

- Contract manufacturing involves having someone else manufacture products while you take on some of the marketing efforts yourself. This saves investment, but again you may be training a competitor.

- Direct entry strategies, where the firm either acquires a firm or builds operations "from scratch" involve the highest exposure, but also the greatest opportunities for profits. The firm gains more knowledge about the local market and maintains greater control, but now has a huge investment. In some countries, the government may expropriate assets without compensation, so direct investment entails an additional risk. A variation involves a joint venture, where a local firm puts up some of the money and knowledge about the local market.

Entry Strategies

Methods of entry. With rare exceptions, products just don’t emerge in foreign markets overnight—a firm has to build up a market over time. Several strategies, which differ in aggressiveness, risk, and the amount of control that the firm is able to maintain, are available:

- Exporting is a relatively low risk strategy in which few investments are made in the new country. A drawback is that, because the firm makes few if any marketing investments in the new country, market share may be below potential. Further, the firm, by not operating in the country, learns less about the market (What do consumers really want? Which kinds of advertising campaigns are most successful? What are the most effective methods of distribution?) If an importer is willing to do a good job of marketing, this arrangement may represent a "win-win" situation, but it may be more difficult for the firm to enter on its own later if it decides that larger profits can be made within the country.

- Licensing and franchising are also low exposure methods of entry—you allow someone else to use your trademarks and accumulated expertise. Your partner puts up the money and assumes the risk. Problems here involve the fact that you are training a potential competitor and that you have little control over how the business is operated. For example, American fast food restaurants have found that foreign franchisers often fail to maintain American standards of cleanliness. Similarly, a foreign manufacturer may use lower quality ingredients in manufacturing a brand based on premium contents in the home country.

- Turnkey Projects. A firm uses knowledge and expertise it has gained in one or more markets to provide a working project—e.g., a factory, building, bridge, or other structure—to a buyer in a new country. The firm can take advantage of investments already made in technology and/or development and may be able to receive greater profits since these investments do not have to be started from scratch again. However, getting the technology to work in a new country may be challenging for a firm that does not have experience with the infrastructure, culture, and legal environment.

- Management Contracts. A firm agrees to manage a facility—e.g., a factory, port, or airport—in a foreign country, using knowledge gained in other markets. Again, one thing is to be able to transfer technology—another is to be able to work in a new country with a different infrastructure, culture, and political/legal environment.

- Contract manufacturing involves having someone else manufacture products while you take on some of the marketing efforts yourself. This saves investment, but again you may be training a competitor.

- Direct entry strategies, where the firm either acquires a firm or builds operations "from scratch" involve the highest exposure, but also the greatest opportunities for profits. The firm gains more knowledge about the local market and maintains greater control, but now has a huge investment. In some countries, the government may expropriate assets without compensation, so direct investment entails an additional risk. A variation involves a joint venture, where a local firm puts up some of the money and knowledge about the local market.