Distribution: Wholesaling and Retailing of Food Products

A large part of the food products value-chain is distribution— (1) efficiently getting the product (2) in good condition to where (3) it is convenient for the consumer to buy it (4) in a setting that is consistent with the brand’s image.

Distribution (also known as the place variable in the marketing mix, or the 4 Ps) involves getting the product from the manufacturer to the ultimate consumer. Distribution is often a much underestimated factor in marketing. Many marketers fall for the trap that if you make a better product, consumers will buy it. The problem is that retailers may not be willing to devote shelf-space to new products. Retailers would often rather use that shelf-space for existing products have that proven records of selling.

Although many firms advertise that they save the consumer money by selling direct and “eliminating the middleman,” this is a dubious claim. The truth is that intermediaries, such as retailers and wholesalers, tend to add efficiency because they can do specialized tasks better than the consumer or the manufacturer. Because wholesalers and retailers exist, the consumer can buy one pen at a time in a store located conveniently rather than having to order it from a distant factory. Thus, distributors add efficiency by:

- Breaking bulk—the consumer can buy small quantities at a time. Consumers can buy a dozen eggs and a quart of milk at one time. Channels move large quantities of foods from farmers, processors, and manufacturers, taking advantages of economies of scale. Distributing. The consumers can buy at a neighborhood store, which in turn can buy from a regional warehouse.

- Carrying inventory

- Financing

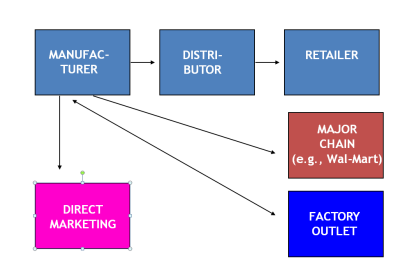

Channel structures vary somewhat by the nature of the product. A large restaurant chain might buy ketchup directly from the manufacturer. The simplest structure is the farmer selling directly to consumers. It is, however, usually inconvenient for the consumer to travel to the farm and for the farmer to sell small quantities to each of many buyers, but occasionally farmers like to supplement their sales by selling at farmers’ markets. Consumers may benefit from fresher products and possibly lower prices, but most of the value here is probably entertainment. Large buyers might be able to buy directly from the farmer—e.g., McDonald’s could buy cows directly in very large quantities and then sell burgers to retail customers.

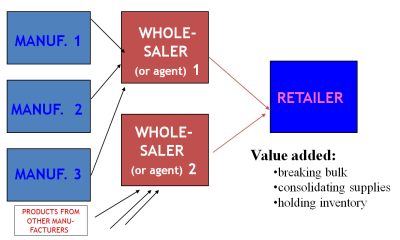

In most cases, however, a wholesaler is involved. This wholesaler buys things from several different manufacturers and delivers those to retailers. A wholesaler may, for example, serve many different retail stores with many brands of cereal, spices, and other food ingredients. The retailer than can buy many different products from the same source, increasing convenience. The wholesaler can buy thousands of cases of Morton salt from the manufacturer and just a few cases at a time to each retailer. The wholesaler will add a margin for this service, but this margin is usually less than what the manufacturer and/or retailer would have to spend in dealing directly with each other.

Manufacturers of different kinds of products have different interests with respect to the availability of their products. For convenience products such as soft drinks, it is essential that your product be available widely. Chances are that if a store does not have a consumer’s preferred brand of soft drinks, the consumer will settle for another brand rather than taking the trouble to go to another store. Occasionally, however, manufacturers will prefer selective distribution since they prefer to have their products available only in upscale stores.

Parallel distribution structures refer to the fact that products may reach consumers in different ways. Most products flow through the traditional manufacturer --> retailer --> consumer channel. Certain large chains may, however, demand to buy directly from the manufacturer since they believe they can provide the distribution services at a lower cost themselves. In turn, of course, they want lower prices, which may anger the traditional retailers who feel that this represents unfair competition.

We must consider what is realistically available to each firm. A small manufacturer of potato chips would like to be available in grocery stores nationally, but this may not be realistic. We need to consider, then, both who will be willing to carry our products and whom we would actually like to carry them. In general, for convenience products, intense distribution is desirable, but only brands that have a certain amount of power—e.g., an established brand name—can hope to gain national intense distribution. Note that for convenience goods, intense distribution is less likely to harm the brand image—it is not a problem, for example, for Haagen Dazs to be available in a convenience store along with bargain brands—it is expected that people will not travel much for these products, so they should be available anywhere the consumer demands them. However, in the category of shopping goods, having Rolex watches sold in discount stores would be undesirable—here, consumers do travel, and goods are evaluated by customers to some extent based on the surrounding merchandise.

Retailing. There are several ways in which retail stores can position themselves. One strategy involves low-cost, low-service. On the opposite side of the spectrum, others may offer high-cost-high-service. Generally, having a clear strategy and position tends to be more effective since "average" stores tend to face a greater scope of competition—e.g., Sears competes both "below" with K-Mart and "above" with Macy’s. K-Mart, in contrast, competes mostly laterally, facing Wal-Mart and Target.

Margins. Stores need to maximize their profits and must consider their margins to do so. Gross margins generally reflect the difference between what a store pays the retailer and what it charges the customer. On the average, this difference in supermarkets is about 25%. (Although there are large differences between product categories, as an illustration, a can that sold for $1.00 might have been bought on wholesale for $0.75). Net margins, in contrast, take into account the allocated costs of running the store—wages, rent, utilities, insurance, and "shrinkage." In grocery stores, these margins are usually less than 5%. Margins can be considered at the unit level—you make $0.35 on a package of salt—or as a percentage of sales—35% if the salt sold for $1.00. Sometimes, it may also be useful to consider margins per unit of space to best allocate retail space to different categories.

There are two theoretical forms of retailing. The "High-Low" method involves selling products at high prices most of the time but occasionally having significant sales. In contrast, the "everyday low price" (EDLP) strategy involves lower prices all the time but no sales. In practice, there are few if any EDLP stores—most stores put a large amount of merchandise on sale much of the time. It has been found that offering lower everyday prices requires a very large increase in sales volume to be profitable.

Slotting Fees. Since retailers are offered many more products than they can carry, they often have a great deal of bargaining power with suppliers. Retailers are often reluctant to accept a new product that may or may not be successful. Often, when a new product is introduced, manufacturers are asked to pay a “slotting” fee to get access to the retailer’s shelves. This may seem unfair at first, but two facts should be considered: (1) The retailer is taking a risk by putting out the product, possibly replacing an existing product on which it has at least broken even. (2) Slotting fees may compensate the retailer for given space to a slow-moving product category. If the retailer could not charge a slotting fee, it might decide to devote most of its shelf-space to major national brands that would “turn” more quickly. That is, on a given “slot,” you might sell fifty packs of Nabisco cookies per day, but only seven of the smaller brand. Ultimately, of course, the slotting fee is at least in part passed through to the consumer, but the slotting fee both allows the retailer to protect itself from risk and maintain a unit selling at lower volumes. It should be noted that price competition in the retail field is intense with very low margins. The money received from slotting fees is part of the store’s total revenue. If no slotting fees were charged, prices on the slow-moving and new products may be lower, but it is unlikely that overall store prices would be lower. Retailers would simply have to charge higher prices on other products and would likely be tempted to drop many low share brands.

Increasing power of retailers. As more and more products compete for space in supermarkets, retailers have gained an increasing power to determine what is "in" and what is "out." This means that they can often "hold out" for better prices and other "concessions" such as advertising support and fixtures. A significant trend in recent years has been toward manufacturers’ "private label" brands—that is, the retailers' own brands competing against the national ones. For example, Del Monte peas may now have to compete against Ralph’s brand of peas in those stores. Although private label brands sell for lower prices than national brands, margins are greater for retailers because costs are lower. For example, it is more profitable to sell a can of peas $1.00 when it cost $0.60 to supply than it is to sell a name brand can at $1.25 when that cost $1.05 at wholesale.

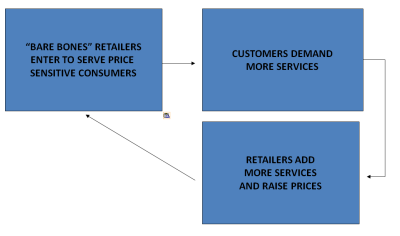

"Wheel of Retailing.” An interesting phenomenon that has been consistently observed in the retail world is the tendency of stores to progressively add to their services. Many stores have started out as discount facilities but have gradually added services that customers have desired. For example, the main purpose of shopping at establishments like Costco and Sam’s Club is to get low prices. These stores have, however, added a tremendous number of services—e.g., eye examinations, eye glass prescription services, tire installation, insurance services, upscale coffee, and vaccinations.

To the extent these services can be added in a cost effective manner, that is a good thing. Ironically, however, what frequently happens is that "room" now opens up for a "bare bones" chain to come in and fill the void that the original store was supposed to have filled! New stores can now come in and offer lower prices before additional, costly services "creep" in. Note that upscaling over time may be an appropriate strategy and that the owner of the "rising" chain may itself want to start another, lower-service division (e.g., Ralph’s may want to own another chain such as Food 4 Less).

Retailing polarity. A number of retailers have tended to go to one extreme or the other—either toward a great emphasis on price or a move toward higher service. Rapid economic growth has made high service retailers more attractive to a growing number of affluent consumers, and less affluent consumers have become more accustomed to intense price competition between different retailers.

Scanner Data. Retailers and manufacturers today are able to make strategic decisions based on information from price scannings at checkout counters. Wal-Mart, for example, has looked at which products tend to be purchased together. At Wal-Mart supercenters which carry both food and traditional products, it was decided to put bananas both in the produce and the cereal sections. Many consumers would get to cereal and realize that they needed bananas. Not all were willing to go back and get them, but bananas will be bought if located next to cereal.

In some cities, a group of consumers agree to participate in a scanner data “panel.” These consumers receive a card much like the loyalty cards available to members of Vons Club. Their purchases are tracked and correlated with media exposure and demographics. This makes certain analyses possible:

- By comparing purchases to television exposure, it is possible to see whether and how many times an ad has been seen. Split cable allows testing whereby half of the cable subscribers see an ad while the other half does not. Sales to those who have and those who have not seen an ad can be compared, or two different advertising themes can be tested.

- The impact of promotional situations—such as whether the brand of interest or a competitor was on sale, whether a coupon was redeemed, or whether any category brand received special display space—can be considered.

- Purchases can be compared to past purchases. This allows for tests of brand loyalty and switching behavior.

- Timing of purchases can be examined. Does a particular product sell higher volumes on certain days?

- How do a particular store’s sales compare to those in other chains? For example, neighborhoods with high concentrations of specific ethnic groups may sell more of certain brands or product categories.